- SurviveJS - Webpack and React

- Introduction

- 1. Webpack Compared

- 2. Developing with Webpack

- 3. Webpack and React

- 4. Implementing a Basic Note App

- 5. React and Flux

- 6. From Notes to Kanban

- 7. Implementing Drag and Drop

- 8. Building Kanban

- 9. Linting in Webpack

- 10. Authoring Libraries

- 11. Styling React

- 12. Troubleshooting

Webpack Compared

You can understand Webpack better by putting it into a historical context. This will show you why its approach is powerful. Back in the day it was enough just to concatenate some scripts together. Times have changed, though. Now distributing your JavaScript code can be a complex endeavor.

This problem has been escalated by the rise of single page applications (SPAs). They tend to rely on various heavy libraries. The last thing you want to do is to load them all at once. There are better solutions and Webpack allows many of those.

The popularity of Node.js and npm, the Node.js package manager, provides more context. Before npm it was difficult to consume dependencies. Now that npm has become popular for front-end development, the situation has changed. Now we have nice ways to manage the dependencies of our projects.

Historically speaking there have been many build systems. Make is perhaps the most known one and still a viable option. In the front-end world Grunt and Gulp have particularly gained popularity. Plugins make available through npm make both approaches powerful.

Grunt

Grunt went mainstream before Gulp. Its plugin architecture especially contributed towards its popularity. At the same time this is the Achilles' heel of Grunt. I know from experience that you don't want to end up having to maintain a 300 line Gruntfile. Here's an example from Grunt documentation:

module.exports = function(grunt) {

grunt.initConfig({

jshint: {

files: ['Gruntfile.js', 'src/**/*.js', 'test/**/*.js'],

options: {

globals: {

jQuery: true

}

}

},

watch: {

files: ['<%= jshint.files %>'],

tasks: ['jshint']

}

});

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-jshint');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-watch');

grunt.registerTask('default', ['jshint']);

};

In this sample, we define two basic tasks related to jshint. It is a linting tool that helps you spot possible problem spots at your source code. We have a standalone task for running it. Also, we have a watcher based task. If we run it, we'll get warnings interactively at our terminal as we edit.

In practice, you would have a lot of small tasks such as these for various purposes such as building the project. The example shows well how these tasks are constructed. An important part of the power of Grunt is that it hides a lot of the wiring from you. Taken too far this can get problematic though. It can be hard to understand well enough what's going on under the hood.

T> Note that grunt-webpack plugin allows you to use Webpack in a Grunt environment. You can leave the heavy lifting to Webpack.

Gulp

Gulp takes a different approach. Instead of relying on configuration per plugin you deal with actual code. Gulp builds on top of the tried and true concept of piping. If you are familiar with Unix, it's the same idea here. You simply have sources, filters and sinks.

Sources match files. Filters perform operations on those (e.g. convert to JavaScript). Finally, it gets passed to sinks (your build directory etc.). Here's a sample Gulpfile to give you a better idea of the approach taken from the project README. It has been abbreviated a bit:

var gulp = require('gulp');

var coffee = require('gulp-coffee');

var concat = require('gulp-concat');

var uglify = require('gulp-uglify');

var sourcemaps = require('gulp-sourcemaps');

var del = require('del');

var paths = {

scripts: ['client/js/**/*.coffee', '!client/external/**/*.coffee']

};

// Not all tasks need to use streams

// A gulpfile is just another node program and you can use all packages available on npm

gulp.task('clean', function(cb) {

// You can use multiple globbing patterns as you would with `gulp.src`

del(['build'], cb);

});

gulp.task('scripts', ['clean'], function() {

// Minify and copy all JavaScript (except vendor scripts)

// with sourcemaps all the way down

return gulp.src(paths.scripts)

.pipe(sourcemaps.init())

.pipe(coffee())

.pipe(uglify())

.pipe(concat('all.min.js'))

.pipe(sourcemaps.write())

.pipe(gulp.dest('build/js'));

});

// Rerun the task when a file changes

gulp.task('watch', function() {

gulp.watch(paths.scripts, ['scripts']);

});

// The default task (called when you run `gulp` from cli)

gulp.task('default', ['watch', 'scripts']);

Given the configuration is code you can always just hack it if you run into troubles. You can wrap existing Node.js modules as Gulp plugins and so on. Compared to Grunt you have a clearer idea of what's going on. You still end up writing a lot of boilerplate for casual tasks, though. That is where some newer approaches come in.

T> gulp-webpack allows you to use Webpack in Gulp environment.

Browserify

Dealing with JavaScript modules has always been a bit of a problem. The language actually didn't have the concept of modules till ES6. Ergo we are stuck in the 90s when it comes to browser environment. Various solutions, including AMD, have been proposed.

In practice, it can be useful just to use CommonJS, the Node.js format, and let the tooling deal with the rest. The advantage is that you can often hook into npm and avoid reinventing the wheel.

Browserify solves this problem. It provides a way to bundle CommonJS modules together. You can hook it up with Gulp. There are smaller transformation tools that allow you to move beyond the basic usage. E.g. watchify provides a file watcher that creates bundles for you during development. This will save some effort and no doubt is a good solution up to a point.

The Browserify ecosystem is composed of a lot of small modules. This way they remind of the Unix philosophy. It is a little easier to adopt than Webpack and in fact, it is a good alternative to it.

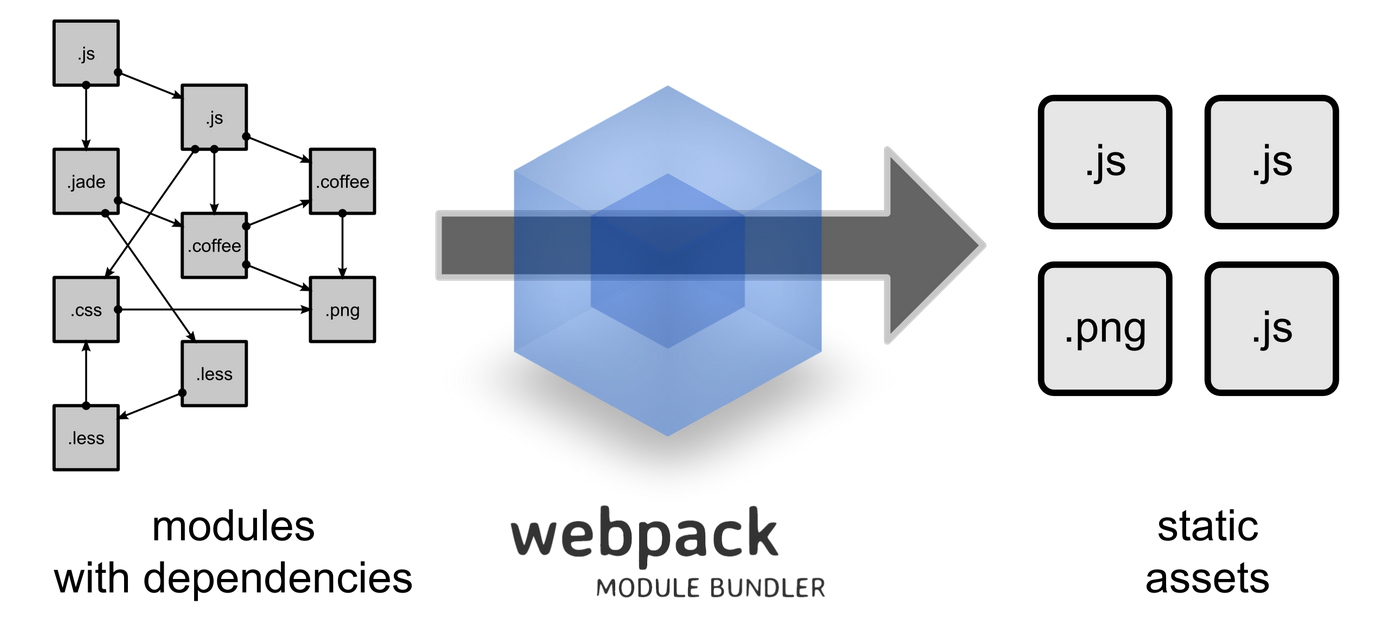

Webpack

You could say Webpack (or just webpack) takes a more monolithic approach than Browserify. You simply get more out of the box. Webpack extends require and allows you to customize its behavior using loaders. You can load arbitary content through this mechanism. This applies also to CSS files (@import). Webpack also provides plugins for tasks, such as minifying, localization, hot loading etc.

All this is based on configuration. Here is a sample configuration adapted from the official webpack tutorial:

webpack.config.js

var webpack = require('webpack');

module.exports = {

entry: './entry.js',

output: {

path: __dirname,

filename: 'bundle.js'

},

module: {

loaders: [

{

test: /\.css$/,

loaders: ['style', 'css']

}

]

},

plugins: [

new webpack.optimize.UglifyJsPlugin()

]

};

Given the configuration is written in JavaScript it's quite malleable. As long as it's JavaScript, Webpack is fine with it.

The configuration model may make Webpack feel a bit opaque at times. It can be difficult to understand what it's doing. This is particularly true for more complicated cases. I have compiled a webpack cookbook with Christian Alfoni that goes into more detail when it comes to specific problems.

Why Webpack?

Why would you use Webpack over tools like Gulp or Grunt? It's not an either-or proposition. Webpack deals with the difficult problem of bundling, but there's so much more. I picked up Webpack because of its support for hot module replacement (HMR). This is a feature used by react-hot-loader. I will show you later how to set it up.

You might be familiar with tools such as LiveReload or Browsersync already. These tools refresh the browser(s) automatically as you make changes. HMR takes things one step further. In the case of React it allows the application to keep state. This sounds simple but it makes a big difference in practice.

Besides HMR Webpack's bundling capabilities are extensive. It allows you to split bundles in various ways. You can even load them dynamically as your application gets executed. This sort of lazy loading comes in handy, especially for larger applications. You can load dependencies as you need them.

With Webpack you can easily inject a hash to each bundle name. This allows you to invalidate bundles on the client side as changes are made. Bundle splitting allows the client to reload only a small part of the data in the ideal case.

It is possible to achieve some of these tasks with other tools. The problem is that it would definitely take a lot more work to pull off. In Webpack it's a matter of configuration. Note that you can get HMR to Browserify through livereactload so it's not a feature that's exclusive to Webpack.

All these smaller features add up. Surprisingly you can get many things done out of the box. And if you are missing something there are loaders and plugins available that allow you to go further. Webpack comes with a significant learning curve. Even still it's a tool worth learning given it saves so much time and effort over the long term.

To get a better idea how it compares to some other tools, check out the official comparison.

Supported Module Formats

Webpack allows you to use different module formats, but under the hood they all work the same way.

CommonJS

If you have used Node.js, it is likely that you are familiar with CommonJS already. Here's a brief example:

var MyModule = require('./MyModule');

// export at module root

module.exports = function() { ... };

// alternatively, export individual functions

exports.hello = function() {...};

ES6

ES6 is the format we all have been waiting for since 1995. As you can see it resembles CommonJS a little bit and is quite clear!

import MyModule from './MyModule.js';

// export at module root

export default function () { ... };

// or export as module function

export function hello() {...};

AMD

AMD, or asynchronous module definition, was invented as a workaround. It introduces a define wrapper:

define(['./MyModule.js'], function (MyModule) {

// export at module root

return function() {};

});

// or

define(['./MyModule.js'], function (MyModule) {

// export as module function

return {

hello: function() {...}

};

});

Incidentally it is possible to use require within the wrapper like this:

define(['require'], function (require) {

var MyModule = require('./MyModule.js');

return function() {...};

});

This approach definitely eliminates some of the clutter. You will still end up with some code that might feel redundant. Given there's ES6 now, it probably doesn't make much sense to use AMD anymore unless you really have to.

UMD

UMD, universal module definition, takes it all to the next level. It is a monster of a format that aims to make the aforementioned formats compatible with each other. I will spare your eyes from it. Never write it yourself, leave it to the tools. If that didn't scare you off, check out the official definitions.

Webpack can generate UMD wrapper for you (output.libraryTarget: 'umd'). This is particularly useful for library authors. We'll get back to this later when discussing npm and library authorship in detail.

Conclusion

I hope this chapter helped you to understand why Webpack is a valuable tool worth learning. It solves a fair share of common web development problems. If you know it well, it will save a great deal of time. In the following chapters we'll examine Webpack in more detail. You will learn to develop a simple development configuration. We'll also get started with our Kanban application.

You can, and probably should, use Webpack with some other tools. It won't solve everything. It does solve the difficult problem of bundling. That's one worry less during development. Just using package.json scripts and Webpack takes you far as we will see soon.